HOW VR WAS USED TO HELP DESIGN THE GLASS OFFICE FIGHTS IN ‘JOHN WICK: CHAPTER 3’

KEANU REEVES VS. NINJAS: THE VIRTUAL PRODUCTION BEHIND ‘PARABELLUM’S’ GLASS HOUSE SHOWDOWN.

Most people will be familiar with the use of concept art to plan out specific scenes and sequences in films. This art can range anywhere from pencil sketches to much more involved Photoshop designs. But what if 2D concept art is not enough?

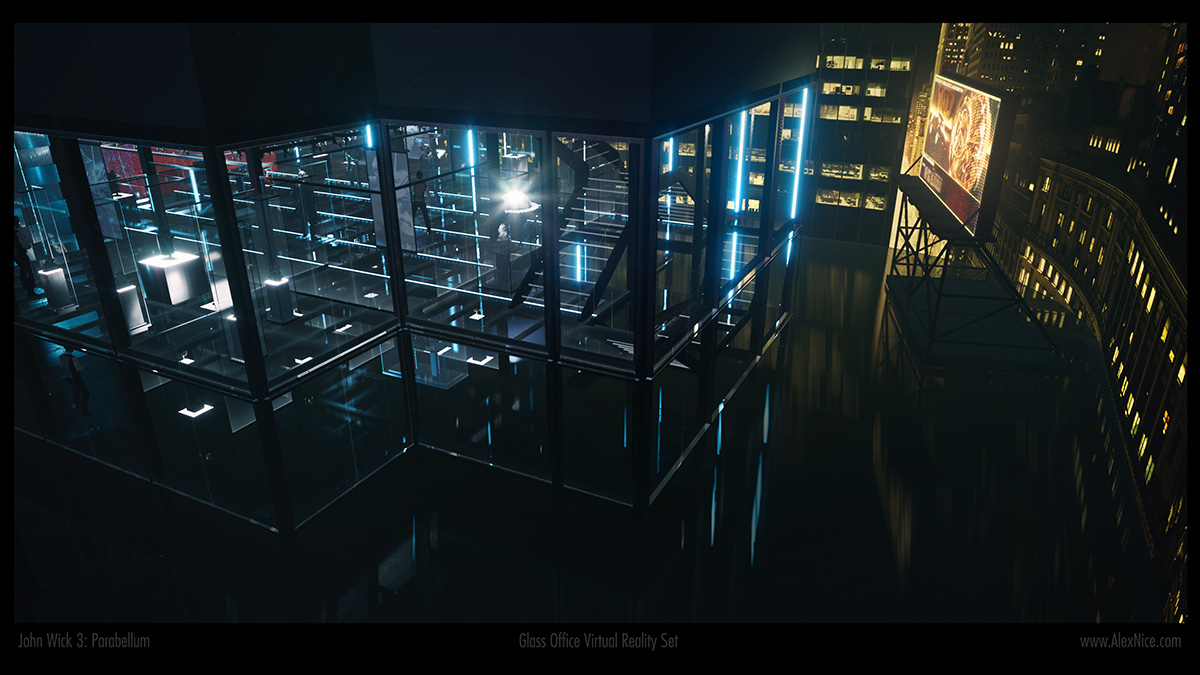

For director Chad Stahelski’s John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum, it was determined that the glass office fight between the central character (played by Keanu Reeves) and a group of ninjas would need something more than just concept art to flesh out the design and action. And that extra something was VR, orchestrated by concept illustrator Alex Nice.

Working under production designer Kevan Kavenaugh, Nice helped design a fully interactive 3D set of the glass office that the filmmakers could view in real-time in VR goggles way before the actual location was constructed as a physical set (the structure reportedly cost $4 million to build). Its virtual version even included proxy fighters, and the ability to mock-fight in VR. This was all done with the aid of Epic Games’ Unreal Engine 4, and some proprietary tools that Nice and partner Matan Abel built. Nice runs down how it all worked, for befores & afters.

More than 2D

Nice had previously worked as an art director at Magnopus, a studio heavily involved in VR and AR experiential projects. VR development had became part of the designer’s art and illustration workflow, particularly in how to design physical spaces. Enlisted as a concept illustrator on Parabellum, Nice fleshed out concept art for the glass office set based on early blueprints and even a small concept model that the production had also crafted.

“It was immediately apparent that a set like this is just such a challenge in planning, especially for a director like Chad who does such high action choreographed scenes,” Nice told befores & afters. “You can imagine how confusing it is, like, where’s the glass wall compared to the other glass walls? Just getting your bearings mentally, even with the plans, was really a big challenge at the very beginning.”

Initially, Nice saw value in using the practical 3D model of the glass office to help with his designs. He actually placed a 360 degree camera inside it, with the footage able to be streamed to a phone using Magic Window. “I could look around like I was inside the glass office. I think that was how the original idea came to build this in VR, because seeing it from that point of view made more sense, instead of looking at it from above the model or on the blueprint plans.”

Jumping into VR

So, Nice decided to build the glass office set completely virtually. This was then realized in Unreal Engine 4, with the game engine’s Blueprints feature enabling Nice and other filmmakers to enter the set in VR and essentially walk around it in real-time, seeing the different camera angles, the effect of all the glass panels and the effect of various lights, including the many neon ones (the complex glass structure inherent in the design was one of the only things that, at the time of the build, proved challenging for the game engine to render at 60hz, given the transparent environment and the many reflections and refractions).

Ultimately, the VR version of the glass office directly informed the practical build, which was carried out on a stage surrounded by greenscreen and a hanging painted backdrop of a city (itself informed by the virtual set).

‘IT’S REALLY COOL TO SEE EVERYONE FREAK OUT IN VR.’

But before any of that physical set construction began, the VR set existed, and people could jump right into it. For example, the cinematographer, Dan Laustsen, could switch between different lighting designs on the virtual set, something he did with a Vive hand controller.

Meanwhile, the set decorator was able to consider furniture and prop placements, or the electricians could establish where to place wiring. Even the producer was given different build options to help establish how much of the set would have to be built physically (i.e. and how much it would cost).

“I put people in the VR, all the way from the top of the movie studio to the construction workers,” outlines Nice. “Every single person on the production pretty much came over to see it and understand what was there.“

“The minute that you put them in the headset and you tell them that they’re going to go in and they see that they’re standing on a piece of glass 30 feet in the air, you see their knees kind of buckle a little bit and kind of freak out! They don’t expect there to be such depth, real spatial depth awareness in there.”

Virtual henchmen

Nice’s work extended to more than just the visualization of the glass set. The build also included a kind of stunt-vis component, where the film’s henchmen were created as avatars that the VR viewer could interact with. This viewer could even ‘punch’ the adversaries and watch them ‘rag-doll’ as a reaction. In fact, Nice gave the VR goggles to the stunt performers before they acted in their scenes on the real set to help them understand the geography of the glass environment.

“The avatars were more just as placeholders to give a sense of scale and movement on the virtual set,” notes Nice. “I downloaded some characters from renderpeople.com, and then I rigged them up in the IKINEMA Orion rig so that I could motion capture them, and I also used mocap data from Mixamo. Just seeing the people in the shots gave a good sense of selling the scene.”

“That was all hugely valuable to the stunt-vis team,” adds Nice, “because then they can really get a sense of things like the stairs and where walls were, and where things were obscured. It actually becomes a really helpful storytelling tool and planning tool way ahead of time. The sooner that you have these guys being able to spatially map out this environment allowed them to do their magic for the film.”

A virtual camera

About half-way through the project, “I heard the cinematographer mention that it would be nice to have a camera in the virtual set to see what the framing would be,” recounts Nice. “So I employed a programmer through an outsourcing website, and together over the span of a few months, me and my partner Matan Abel developed a tool in Unreal that let you walk around within the scene and then hit a button on the controller, which was basically a camera that let you switch between the lenses. It was similar to walking around and seeing it on the monitor, but you were actually in VR holding the camera.”

The tool allowed for scene capture, depth of field and lens cycling within UE4. A key feature of this virtual camera was also that a full-frame preview window of what the VR camera saw was displayed on a PC monitor, allowing other members of the production team to see what the director or cinematographer wanted to focus on.

“For example,” says Nice, “while in the virtual set, the director or DOP could point my VR camera at a location and say, ‘I want to add a glass wall here for Keanu to shoot though,’ and the film department could see and acknowledge the note.”

While the majority of Nice’s work for Parabellum remained traditional production art – using both 2D and 3D tools – he is excited about adding VR to an ever-expanding toolset of design tools.

“It’s just a really great thing, to watch the reactions of people going in there in VR,” Nice shares. “You just see some of the creative juices flowing when they go in. They can say, ‘Wow, we can shoot from here, I can go down here, and get this angle and it will have more impact.’”

“It’s really cool to see everyone freak out in VR. They just smile immediately – it’s almost like they’re on a ride even though it’s a virtual film set.”

Get exclusive content, join the befores & afters Patreon community

0 comentarios:

Publicar un comentario